| أنت زائر للمنتدى رقم |

.: 12465387 :.

|

|

| | The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies |  |

| | | كاتب الموضوع | رسالة |

|---|

salim 1979

التميز الذهبي

تاريخ الميلاد : 27/05/1979

العمر : 45

الدولة : الجزائر

عدد المساهمات : 5285

نقاط : 100012179

تاريخ التسجيل : 06/11/2012

|  موضوع: The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies موضوع: The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies  الإثنين نوفمبر 12, 2012 11:17 pm الإثنين نوفمبر 12, 2012 11:17 pm | |

| The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies

The 'level of analysis concept5 and how it came into international relations theory :

In the social universe,events often hâve more than one cause, and causes can be found in more than one type of location . For example, it is easy to find statement like : 'The second world war was cosed by french insecurity, German revenchism, and a fatally weakend balance of power mecanism'. This multi-causality may reflect explanation that are ali in the same type of location. In the exemple juste given, the french and german causes are in the same type of location, both conserning the behaviour and motive of states. But a weak balance of power is a feature of the international System as whole, a différent type of location for explaining the war than those derived from the behaviour of individual states . Arguing that the war was caused by Hitler would be a third type of location 9 différent from the states - and system-based ones , though of the same type as: the second world war caused by Chamberlain ( or Staline or Rooselveit ). 'The level of analysis problem is about how to identify and treat différent types of location in which sources of explanation for observedphenomena can be found9.

The issue of levels of analysis came in to international relations during the 1950s as part of the broader impact of the behavioural movement, which was trying to introduce the methodology and rigour of the natural sciences into social science . the main cotisem was to encorage a more positivist, scientifïc approach in the discipline , stressing observed facts, quantitative measurements , hypothesis-testing , and the developement of cumulative theory. This required that one specify and differentiate the sourses of one's explantion . it also resulted in part from the impact of gênerai Systems theory as a way of thinking about a wide range of physical and social phenomena.

The "behavioral revolution c meshed with a long-stading epistemologecal debate in the social sciences about two prirriary approaches to understanding social events : atomistic and holistic . In international relations thèse two approaches are more commoniy known as rerductionist and systemic after the usage of Kenneth Waltz. Atomism/reductionism is thé .iiighJy succesful methodology of the natural scienses , and requires the fragmentation of a subject into its component parts. In the reductionist approach, understanding improves as one is abîe to subdivide and explain the component parts of the system ever more finely , as has been done with such astounding succès in physics , chemistry , astronomy and biology during the twentieth century. A

1

The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies

A holistic/systemic approach rests on the premise that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, and that the behavior and even construction of the parts are shaped and moulded by structures embedded in the System it self Where the effect of structure is strong , a reductionist approach is inadequate , and on this basis holism established a claim to a distinctive social science approach to analysis. I

Levels of analysis made a strong Impact on international relations not least because the idea of levels seemed to fit easily and neatly in to the organization of the discipline’s subject matter in terms of individuals, sîates and Systems. Three US writers were main irresponsible for brining the level of analysis problem in to mainstream of thinking about international relations theory ; Kenneth Waltz, Morton Kaplan and David Singer. Wajfcz made the most durable impact by demonstrating the power of an explicitly ievelled' approach in his still vvidely read 1959 classic (based on his 1954 Ph.D . thesis ) Man, the State and War An that book Waltz unpacked the classical literature on war, and showed how ail of it could be organized around three distinct 'images' , each reflecting a différent location and type of explanation . Some writers explained war by human nature, others by the nature of states \ and others by nature of the international System. Waltz’s scheme separated out the international system, and particularly its anarchie structure, as a location of explanation in its own right and it was this development more than any other that shaped the development of levels of analysis thinking in the discipline.

Morton Kaplan picked it up in his Î957 book system and process in international politics, which started a vogue for system theory. Most of this took the form of attempts to construct typologies of international System types, usually on the basis of patterns in the distribution of power and/or configuration of alliances, and then to infer hypotheses about behavior from these patterns. Whereas Waltz favored the system level as the dominate source of explanation, Kaplan argued more in favor of the dominance of the state level, and this began a debate which continues to the present day. One effect of this heightened interest in levels was to search for ways of theoretically comprehending what 'international system meant. Its ontological meaning was clear enough (the sum of ail its parts and their interactions), but only if something more than the sum of the parts - the structure or essence of the system - could be specified, could it be used as a basis for explaining international relations. The system levels also had the attraction that it increased the distinctiveness of international relations as a field, and give it some hope of establishing a claim to be a discipline in its own right. Singer’s contribution was less substantive, but his 1960 review of Waltz's book, and his 1961 essay 'The Level of Analysis Problem in International Relations’ were influential in moving awareness of the problem, and used of the term 'levels of analysis ', into the centre of theoretical debate in the field.

These three writers opened the debate about levels of analysis, but they certainly did not close it. Once the importance of levels of analysis to any coherent understanding of

2

The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies 3

International relations was accepted, two issues arose:

1 - How many, and what, level of analysis should there be for international relations? 2- by what criteria can these levels be defined and differentiated from one another ? On- neither of these issues is the debate settled. A third issue, once a levels scheme is established, is how one puts the pieces back together again to achieve a holistic understanding. Debate on this has only just begun.

How Many and What Levels ?

"The early stages of the levels of analysis debate in international relations projected an unwarranted impression of simplicity about the whole idea. The neat fît between the idea of levels, and the natural division of the subject matter into individual, states and System, seems largely to have forestalled any intense enquiry into the concept of levels itself.

In practice, the discipline has proceeded along very pragmatic and simple lines, asking few fundamental questions, and not straying far beyond its starting point. Levels of analysis in international relations has been closely tied to idea of system , defined as 'a set of units interacting within a structure '. Using this approach , to candidates for levels are imediately obvious : the units and the structure of the System. Waltz's original formulation used three levels : the individual, the unit of state, and the System itself in terms of its anarchie structure. Singer proffered two levels, system and states, but then hedged his bets by saying : cit must be stressed that we have dealt here only whit two of the more common orientations, and that many others are available and perhaps even more I fruitful potentially than either of those selected here'. In his letter work , Waltz ends up

dose to singer's original1 position , though for different reasons. Arguing from the general distinction between reductionist and holist theories, Waltz lumps together 'theories of international politics that concentrate causes at the individual or national level\ classifying both as 'reductionist'.

Theories that conceive causes operating at the international level he classifies as 'systemic\ In logic I this approach privileges the epistemological over the ontological, but in practice it simply blurred the distinction :

system and unit could be (and were) seen as both objects of analysis and sources of explanation.

Following in the track set by Waltz and Singer, most international relation scholars accept at ieast three levels : individual (often focused on decision -makers ), unit (usually state, but potentially any goup of humans designated has an actor) and system . As yurdusev argues this basic classification is inclusive , even though it can be further subdivided , especially in the meddle level. Some writers insert a bureaucratie level between individual and unit. Others insert a 'process' level between unit and system to capture the difference between explanation based on the nature of the units, and those based on the dynamics of interactions among units (Goidmann, buzan and little), others that the system level should be divided into two distanct levels, either structure and Interaction capacity,(deièned as the level of transportation,communication and organization capability in the system ) or 'international9 and *world' (Goldstein). Some hâve their own schemes of levels that do not fit well with more conventional views: Rosenau suggests five - idiosyncratic, role \ governmental, societal and systemic.

The Level of Analysis m International Relations Theory Studies 4

Much of this confusion can be removed by observing that what underlies thèse proposais is an unresolved dispute between two overlapping schemes for identifying what 'leveis' are supposed to represent One (ontological) sees leveis as being about 'différent units of analysis\znà the other (epistemological) sees them as being about 'the types of variables than explain a particular unit s behaviour '. Yurdusev proposes distinguishing between units of analysis and 'leveis of abstraction' in methodology (philosophical, theoretical and empirical).

Thefirst., and simpler, scheme focuses on leveis as units of analysis organized on the principle of spatial scale (small to large , individual to system). The term 'leveis' does sugges a range of spatial scales or 'heights'.In this sensé, leveis are locations where both outcomes and sources of explanation can be located. They are ontological refrents rathar than sources of explanation in and of themselves . The introdiction of ana^sis in to international relations by waltz , Singer and K api an could be conceived in thèse terms I and much of the debate about leveis of analysis has de facto taken within this framework. In this perspective ,levels range along a spectrum from individual, throwgh bureaucratie and state, to région (subsystem) and system.

In the second scheme, leveis are understood as defferent types or sources of explanation for observed phenomena. In principle , anything that can be established as a distinct source of explanation can qualify.

Ih practice, debate in international relations has largely developed around three ideas :

1- Interaction capacity : definde generally as the level of transportation , communication and organizarion capability in the system . Interaction capacity focuses on the types and intensifies of interaction that are possible within any given unit / subsystem/system ai the point of analysis : how much goods and information can be moved over what distances at what speed and what costs.

2- Structure : defined generally as the principle by which units within a system are arranged . Structure focuses on how. units are differentiated from one another , how^they are arranged into a system , and how they stand in relation to one another in terms of relative capabiïities.

3- Process : defïnd generally as interactions among units , particularly durable or récurrent in patterns in those interactions . Process focuses on how units actually interact with one another within the constraints of interaction capacity and structure , and particularly on durable or récurrent patterns in the dynamics of interaction.

Each of these sources can itself be subdivided into more specific classifications along the lines of Waltz's three tiers of structure.

Levels in this sense are not in and of themselves units of analysis . The two schemes can be integrated as a matrix in which each unit of level of analysis contains , in principle , ail of the sources or types of explanation . Thus structures, process and interaction capacity can be found as sources of explanation in individuals , states and the

The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies

International System. Differentiating units of analysis and sources of explanation resolves much of the incoherence about how many and what levels.

Taking ail of this discussion into account, one version of definitions and differentiations for levels of analysis in international relations theory might begin to arranged as in the following figure :

| |

|   | | salim 1979

التميز الذهبي

تاريخ الميلاد : 27/05/1979

العمر : 45

الدولة : الجزائر

عدد المساهمات : 5285

نقاط : 100012179

تاريخ التسجيل : 06/11/2012

|  موضوع: رد: The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies موضوع: رد: The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies  الإثنين نوفمبر 12, 2012 11:30 pm الإثنين نوفمبر 12, 2012 11:30 pm | |

| Perspectives on World Politics

Third edition

Edited by Richard Little and Michael Smith

Third edition published 2006 Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York

Reflections on war and political discourse: realism, just war, and feminism in a nuclear age

Jean Bethke Elshtain

Source: Political Theory, vol. 13, no. 1 (1985), pp. 39 –57.

Elshtain accepts that the study of international relations and war has been dominated by a realist tradition, despite the existence of the long-standing rival just war tradition.

She asserts, however, referring to the work of Hannah Arendt, that a feminist perspective not only makes it

possible to deconstruct realist rhetoric and reveal its inconsistencies, but also can be used to open up a new and

more hopeful line of discourse about war and international relations.

Just wars as modified realism

In a world organized along the lines of the realist narrative, there are no easy ways out.

There is, however, an alternative tradition to which we in the West have sometimes repaired either to challenge or to chasten the imperatives realism claims merely to describe and denies having in any sense wrought.

Just war theory grows out of a complex genealogy, beginning with the pacifism and with drawal from the world of early Christian communities through later compromises with the world as Christianity took institutional form. The Christian saviour was a ‘prince of peace’ and the New Testament Jesus deconstructs the powerful metaphor of the warrior central to Old Testament narrative. He enjoins Peter to sheath his sword; he devirilizes the image of manhood; he tells his followers to go as sheep among wolves and to offer their lives, if need be, but never to take the life of another in violence. From the beginning, Christian narrative presents a pacific ontology, finding in the ‘paths of peace’ the most natural as well as the most desirable way of being. Violence must justify itself

before the court of nonviolence.

Classic just war doctrine, however, is by no means a pacifist discourse. St Augustine’s The City of God, for example, distinguishes between legitimate and illegitimate use of collective violence. Augustine denounces the Pax Romana as a false peace kept in place by evil means and indicts Roman imperialist wars as paradigmatic instances of unjust war.

But he defends, with regret, the possibility that a war may be just if it is waged in defense of a common good and to protect the innocent for certain destruction. As elaborated over the centuries, noncombatant immunity gained a secure niche as the most important of jus in bello rules, responding to unjust aggression is the central jus ad

bellum. Just war thinking requires that moral considerations enter into all determinations of collective violence, not as a post hoc gloss but as a serious ground for making political judgments.

In common with realism, just war argument secretes a broader world-view, including a vision of domestic politics. Augustine, for example sees human beings as innately social.

It follows that all ways of life are laced through with moral rules and restrictions that provide a web of social order not wholly dependent on external force to keep itself intact.

Augustine’s household, unlike Machiavelli’s private sphere, is ‘the beginning or element of the city’ and domestic peace bears a relation to ‘civic peace’. 4 The sexes are viewed as playing complementary roles rather than as segregated into two separate normative systems governed by wholly different standards of judgment depending upon whether one is a public man or a private woman. […]

My criticisms of just war are directed to two central concerns: one flows directly from just war teaching; the other involves less explicit filiations. I begin with the latter, with cultural images of males and females rooted, at least in part, in just war discourse. Over time, Augustine’s moral householders (with husbands cast as just, meaning neither absolute nor arbitrary heads) gave way to a discourse that more sharply divided males and females, their honored activities, and their symbolic force. Men were constituted as just Christian warriors, fighters, and defenders of righteous causes. Women, unevenly and variously depending upon social location, got solidified into a culturally sanctioned vision of virtuous, nonviolent womanhood that I call the ‘beautiful soul’, drawing upon Hegel’s Phenomenology.

The tale is by no means simple but, by the late eighteenth century, ‘absolute distinctions between men and women in regard to violence’ had come to prevail. 5 The female beautiful soul is pictured as frugal, self-sacrificing, and, at times, delicate. Although many women empowered themselves to think and to act on the basis of this ideal of female virtue, the symbol easily slides into sentimentalism. To ‘preserve the

purity of its heart’, writes Hegel, the beautiful soul must flee ‘from contact with the actual world’. 6 In matters of war and peace, the female beautiful soul cannot put a stop to suffering, cannot effectively fight the mortal wounding of sons, brothers, husbands, fathers. She continues the long tradition of women as weepers, occasions for war, and keepers of the flame of nonwarlike values.

The just warrior is a complex construction, an amalgam of Old Testament, chivalric, and civic republican traditions. He is a character we recognize in all the statues on all those commons and greens of small New England towns: the citizen-warrior who died to preserve the union and to free the slaves. Natalie Zemon Davis shows that the image of warlike manliness in the later Middle Ages and through the seventeenth century, was but

one male ideal among many, having to compete, for example, with the priest and other religious who foreswore use of their ‘sexual instrument’ and were forbidden to shed blood. However, ‘male physical force could sometimes be moralized’ and ‘thus could provide the foundation for an ideal of warlike manliness’. 7 This moralization of collective male violence held sway and continues to exert a powerful fascination and to

inspire respect.

But the times have outstripped beautiful souls and just warriors alike; the beautiful soul can no longer be protected in her virtuous privacy. Her world, and her children, are vulnerable in the face of nuclear realities. Similarly, the just warrior, fighting fair and square by the rules of the game, is a vision enveloped in the heady mist of an earlier time. War is more and more a matter of remote control. The contemporary face of battle is

anomic and impersonal, a technological nightmare, as weapons technology obliterates any distinction between night and day, between the ‘front’ and the ‘rear’. […]

Few feminist writers on war and peace take up just war discourse explicitly. There is, however, feminist theorizing that may aptly be situated inside the broader frames of beautiful souls and just warriors as features of inherited discourse. The strongest contemporary feminist statement of a beautiful soul position involves celebrations of a ‘female principle’ as ontologically given and superior to its dark opposite, masculinism.

(The male ‘other’ in this vision is not a just warrior but a dangerous beast.) The evils of the social world are traced in a free-flowing conduit from masculinism to environmental destruction, nuclear energy, wars, militarism, and states. In utopian evocations of ‘cultural feminism’, women are enjoined to create separate communities to free themselves from the male surround and to create a ‘space’ based on the values they embrace. An essentially Manichean vision, the discourse of feminism’s beautiful souls contrasts images of’caring’ and ‘connected’ females in opposition to ‘callous’ and disconnected’ males. Deepening sex segregation, the separatist branch of cultural feminism draws upon, yet much exaggerates received understandings of the beautiful soul.

A second feminist vision indebted implicitly to the wider discursive universe of which just war thinking is a part features a down-to-earth female subject, a soul less beautiful than virtuous in ways that locate her as a social actor. She shares just war’s insistence that politics must come under moral scrutiny. Rejecting the hard-line gendered epistemology and metaphysic of an absolute beautiful soul, she nonetheless insists that ways of knowing flow from ways of being in the world and that hers have vitality and validity in ways private and public. The professed ends of feminists in this loosely fitting frame locate the woman as a moral educator and a political actor. She is concerned with ‘mothering’, whether or not she is a biological mother, in the sense of protecting society’s most vulnerable members without patronizing them. She thinks in terms of human dignity as well as social justice and fairness. She also forges links between ‘maternal thinking’ and pacifist or nonviolent theories of conflict without presuming that it is possible to translate easily particular maternal imperatives into a public good.

The pitfalls of this feminism are linked to its intrinsic strengths. By insisting that women are in and of the social world, its framers draw explicit attention to the context within which their constituted subjects act. But this wider surround not only derogates maternal women, it bombards them with simplistic formulae that equate ‘being nice’ with ‘doing good’. Even as stereotypic maternalisms exert pressure to sentimentalize, competing feminisms are often sharply repudiating, finding in any evocation of ‘maternal thinking’ a trap and a delusion. A more robust concept of the just (female) as citizen is needed to shore up this disclosure, a matter I take up below.

| |

|   | | | | The Level of Analysis in International Relations Theory Studies |  |

|

مواضيع مماثلة |  |

|

| | صلاحيات هذا المنتدى: | لاتستطيع الرد على المواضيع في هذا المنتدى

| |

| |

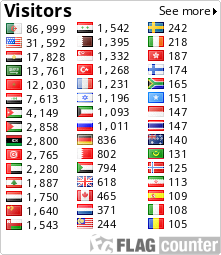

| | Like/Tweet/+1 | زوار المنتدى بالأعلام

|

|